“My goal for this year is …” The beginning of a new calendar year is a natural time for resolutions, goal setting, and fresh beginnings. While well intentioned, both experience and research indicate that the majority don’t achieve their desired outcomes.

While there are many possible reasons for this, the difference between reaching a goal or not may be as straight forward as using a map. We think a map (yes they were actually printed on foldable paper) is a very useful tool and metaphor for how individuals, teams, and organizations navigate from one point to another.

Maps show the routes (roads) available, present standardized information about those routes (local road or highway), and provide an estimate of how far the start point is from the destination (mileage scale). The navigator picks the optimum route (based on speed, sightseeing, where relatives or friends live, etc.) and sets off along the charted course. The goal? Stay on the route! If followed as closely as possible, there should be no doubt the vehicle will arrive at its destination.

Imagine you have created the following plan (map) for weight loss:

Starting point: 165 pounds.

Destination: 150 pounds.

Best route: Consume 1500 calories a day, reduce carbs, increase protein, and walk (briskly) for 30 minutes daily.

Doing the math: Destination will be accomplished in 6 weeks. Ready? Set? Go!!

After six weeks, did you reach the destination? For many, the answer is no. Parties, friends, a new bakery, or other roadblocks get in the way.

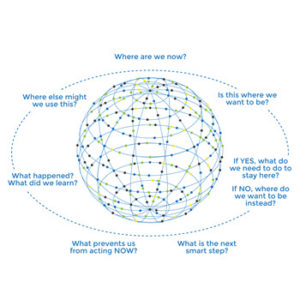

Notice the differences in both visualizing and employing the Complexity Space™ Framework “Navigation Process” (CSF-NP):

- The map is ringed by questions

- There are no directional arrows

- Everything is connected to everything else

- There is no scale

- There are no differentiations between the routes

We think this is a more realistic representation of how change is navigated in complex systems. Something happens (a “Disruption” in the CSF) that causes the person/team/organization to find themselves located at some point in the graphic above.

Examples of disruptions might include:

- A best practice is shared by another team or announced in the industry

- Internal or external customers suggest/demand a change

- The annual budgeting/goal setting/strategic planning process is implemented and gaps/opportunities are identified

Once oriented in the Navigation Process, the parties involved often (but not always) start their journey towards change by moving clockwise from wherever they are. This sequential flow has much in common with traditional models like DMAIC or PDCA in the process improvement world.

Then reality presents a detour. Something new and unexpected occurs. People change. The surrounding environment or competitors change. A step forward takes longer than anticipated or is never taken. In a traditional plan, this would cause consternation. The plan is no longer usable and has to be discarded! Whose fault is it?

In the CSF-NP, those same disruptions are understood as a reality of working within complex systems. Rather than cause alarm, they invite conversation and learning. In the CSF Navigation Process, there is no negative connotation associated with moving “backwards” in a counter-clockwise direction. In fact, it is OK to move in a scattered direction among the various questions. Notice. Synthesize. Learn. Experiment. Repeat.

“I may not have gone where I intended to go, but I think I have ended up where I needed to be.”

― Douglas Adams, The Long Dark Tea-Time of the Soul

Starting point: 165 pounds.

Destination: 150 pounds.

Initial Experiment: Consume 1500 calories a day, reduce carbs, increase protein, and walk (briskly) for 30 minutes daily.

If everything goes perfectly, the best case scenario is: destination will be accomplished in 6 weeks.

Disruption: Attend wedding and eat/drink/celebrate too much. Notice: Self-control goes out the window with regards to calories – and it was a GREAT Time! Synthesize: I have a history of overdoing it when food is presented to me (hot appetizers) and readily available (buffet). Learning: need to be more conscious of intake in these situations. Experiment: Bring an index card and pen to next social function. Make a mark every time I take a hot appetizer or make a trip to the buffet. Ask myself if I really want it. If yes, take it and eat it slowly! Hope that taking the “grab one if it’s offered” response off of autopilot will result in fewer calories consumed.

Is this approach “guaranteed” to work? Of course not. Does it minimize unproductive blaming, maximize learning, and recognize the reality of complex change? We think so.

We hope this more fluid, adaptive approach to navigating change offers you new possibilities for thought and action. To learn more about the Complexity Space™ Framework, visit our website at www.complexityspace.com or purchase our book, “Complexity Works!” at https://tinyurl.com/Complexity-Works.