In her McKinsey Quarterly article, “Creating Value in the Age of Distributed Capitalism,” Shoshana Zuboff writes, “What’s the difference (between innovations and mutations)? Innovations improve the framework in which enterprises produce and deliver goods and services. Mutations create new frameworks.”

This is a powerful distinction. “Doing what we currently do better” is different (by the way, not “better or worse” — both of these may be needed and/or desirable based on the situation) than “doing something brand new.” We encourage a deeper understanding of the Strategic Patterns that both create and need to be created to move between three States that are inherent in all business systems.

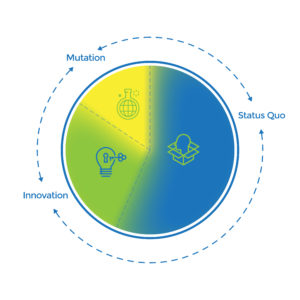

We have identified States in the Complexity Space™ Framework (CSF), as an Ecosystem level view of Strategic “Meta Patterns” – the organization’s business intent. Some organizations work hard to stay the same; to maintain the Status Quo. Other teams and organizations have as their goal to change the status quo; pursuing Innovation – making evolutionary changes to better cope with internal or external needs for change. Yet other organizations challenge themselves to create revolutionary change – inventing something new; a brand new paradigm, a new suite of products, services, or technology. We’ve named this third set of objectives Mutation.

We have identified States in the Complexity Space™ Framework (CSF), as an Ecosystem level view of Strategic “Meta Patterns” – the organization’s business intent. Some organizations work hard to stay the same; to maintain the Status Quo. Other teams and organizations have as their goal to change the status quo; pursuing Innovation – making evolutionary changes to better cope with internal or external needs for change. Yet other organizations challenge themselves to create revolutionary change – inventing something new; a brand new paradigm, a new suite of products, services, or technology. We’ve named this third set of objectives Mutation.

![]() Another useful way to consider these distinctions graphically adapts Ralph Stacy’s “Landscape Diagram,” where the distinctions might look something like the image on the left. In the lower left-hand corner is the “status quo.” This is a system’s “business as usual” space, where everyone involved knows what to do and what results to expect. This space is comfortable and predictable. This is the part of the landscape where, “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

Another useful way to consider these distinctions graphically adapts Ralph Stacy’s “Landscape Diagram,” where the distinctions might look something like the image on the left. In the lower left-hand corner is the “status quo.” This is a system’s “business as usual” space, where everyone involved knows what to do and what results to expect. This space is comfortable and predictable. This is the part of the landscape where, “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

Sometimes, either internal or external forces or both make the status quo unacceptable. The stimulus or disruptions for those changes might come from either inside or outside of the organization. Within the Complexity Space™ Framework, disruptions are the triggers that can instigate “disrupting patterns” for change in the Ecosystems States.

Organizations strive for increases in quality, cost, timeliness, compliance, customer satisfaction, or employee satisfaction. Perhaps an employee survey returns disappointing results, or an internal or external audit highlights significant non-conformances. In these situations, systems are motivated to move beyond the “status quo” to “doing what they’re currently doing better.”

Some organizations have been successful in turning that mindset into a system-wide pattern in its own right. They have embedded it in their Ecosystem Dimensions. “Continuous improvement” becomes part of their culture; part of their shared motivation; part of their history.

Yet there are times when a culture of innovation can be dangerous to a system’s long term survival and prosperity. Another piece of folk wisdom is that “there is nothing more frustrating than doing efficiently a task which should have never been done at all.” Imagine you manufacture 3.5” floppy diskettes (Remember them?). You are proud of your product and continuously innovate to make the cases more sturdy, the protective slides more reliable, the colors more attractive and the packaging more eco-friendly. How did that work for you? How about being a Swiss analog watch maker in the 1970s – just before the invention of the quartz movement, battery-operated watch?

Other disruptions jolt the system. They are “paradigm shifts”; disruptive technologies; “disturbances in the force” as Obi Wan Kanobe said in Star Wars.  These shocks to the existing patterns require very different responses than “do what we currently do better.” They move us to the upper right-hand quadrant of the Landscape Diagram. Here, there is little agreement about what to do, and even less of idea of whether what we try will work. The very patterns that served us so well before may now serve as constraints – preventing us from engaging in the bold new thinking needed for survival and success.

These shocks to the existing patterns require very different responses than “do what we currently do better.” They move us to the upper right-hand quadrant of the Landscape Diagram. Here, there is little agreement about what to do, and even less of idea of whether what we try will work. The very patterns that served us so well before may now serve as constraints – preventing us from engaging in the bold new thinking needed for survival and success.

These distinctions create several challenges and opportunities for your complex adaptive system:

- Where are you now in the Landscape Diagram? An assessment of of how the organization’s Ecosystem Dimensions support or antagonize the objective to move from one State to another helps catalyze and focus this conversation.

- Is disruption needed or desired? If so, which type? Answering this question will require great discernment by the organization. Jim Collins, in his book, “Built to Last,” states that organizations need to “take a hard, unflinching look at the reality of their marketplace.” This is a great time to utilize the principles and tools of engagement and “liberating structures.”

- If disruption is needed, how will you go about the process of creating it? Commanding the organization to shift paradigms seems a lot like making the statement, “On the count of three, I want you to be spontaneous. One … Two … Three!” A more effective strategy is to focus attention on the organization’s eco-levers which we name Catalysts in the CSF. Making deliberate interventions to shift the engagement, connections, experiments, diversity, questions, and leadership within the system will result in short-term shifts to the organization’s relationships. These, in turn, provide the potential for shifting the dimensions of the longer-term ecosystem dimensions.

- Finally, how will you know it is working? One of the “inconvenient truths” of complex systems is that they are continuously emerging, self-organizing, and adapting. Even as your organization is doing the steps above, it continues to operate in a larger context that is continually influencing it and being influenced by it.

The answers to these questions create the conditions for organizations to move between States with a new set of “data” that provides insights into the behavorial pattern shifts throughout the system. Zubroff’s conclusion aligns with our thinking and reinforces the need for organizations to develop a different set of evaluations to respond to the changing world around them:

The pattern of change is one of overlapping and interwoven fields of transition rather than clean, unidirectional breaks. For those of us living through these transitions, they can be confusing and frustrating; resources invested in innovation serve only to fix what was, bringing us no closer to the future. But these times are also rich with unique opportunities for companies able to decipher the emerging pattern of mutation and to convert that understanding into new business models that support the complex needs of the 21st-century individual.

We Invite you to share your stories, questions and even disagreements with our articles because that is the only way we can continue to make sure Complexity Works!

Learn more about the Complexity Space™ Framework, with our book, “Complexity Works!” at https://tinyurl.com/Complexity-Works.